Modes

Contents

Modes#

A Duckiematrix network can run in two modes:

realtime mode

simulation (or gym) mode

Realtime mode#

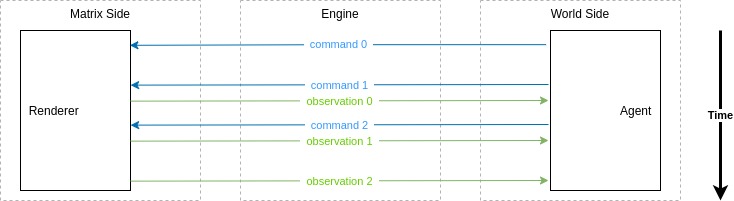

Fig. 5 Sequence diagram of a simple Duckiematrix network running in realtime mode#

In realtime mode, the matrix side and world side work asynchronously with respect to each other.

Agents on the world side can send inputs to the matrix side as fast as they want and the matrix side will consume them as fast as it can.

If the matrix side does not manage to keep up with the agents, some commands will be dropped and never reach it.

Similarly, sensors in the renderers will (try to) produce data at the sensor’s frequency, regardless of how much data the agents can process. In fact, neither side will care whether there is someone listening on the other side. Figure Fig. 5 shows an example of a Duckiematrix network in which an agent and renderer produce outputs asynchronously from each other.

This is exactly what happens with real robots, so it is a very interesting mode to have. While this is the mode that most closely resembles the real behavior of a robot and an agent, it evolves with dynamics that are non-deterministic, meaning that experiments run in realtime mode are not reproducible. Therefore, the scientific community prefers systems that run in synchronous mode.

The job of the engine, in this case, is to run the physics engine on the commands from the world side whenever they are available and bridge data from the matrix side over to the world side.

Simulation (gym) mode#

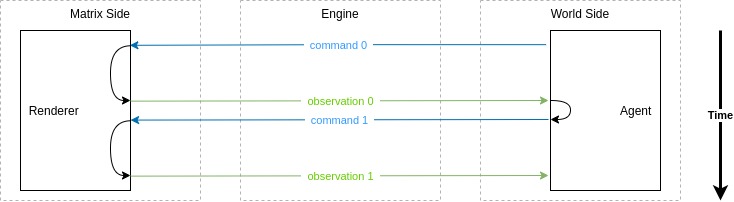

Fig. 6 Sequence diagram of a simple Duckiematrix network running in simulation mode#

The simulation (or gym) mode is synchronous.

Starting from the matrix side, robots will produce their observations (sensor readings).

The engine will then collect and send these observations as a whole to the world side.

The renderers will then be paused until the world side has produced all of its commands.

The engine will then collect these commands and run the physics engine, which will act on these commands.

An updated state of the world is sent to the renderers, which will start producing another batch of observations.

Figure Fig. 6 shows an example of a Duckiematrix network in which an agent and a renderer are kept in sync by the engine.

The strenuous job performed by the engine in this case guarantees that all of the renderers start a batch of rendering/sensing only once all the robots in the scene have received a command from the world side. Overall performance in simulation mode is greatly reduced compared to realtime mode, due to the synchronicity of the events.